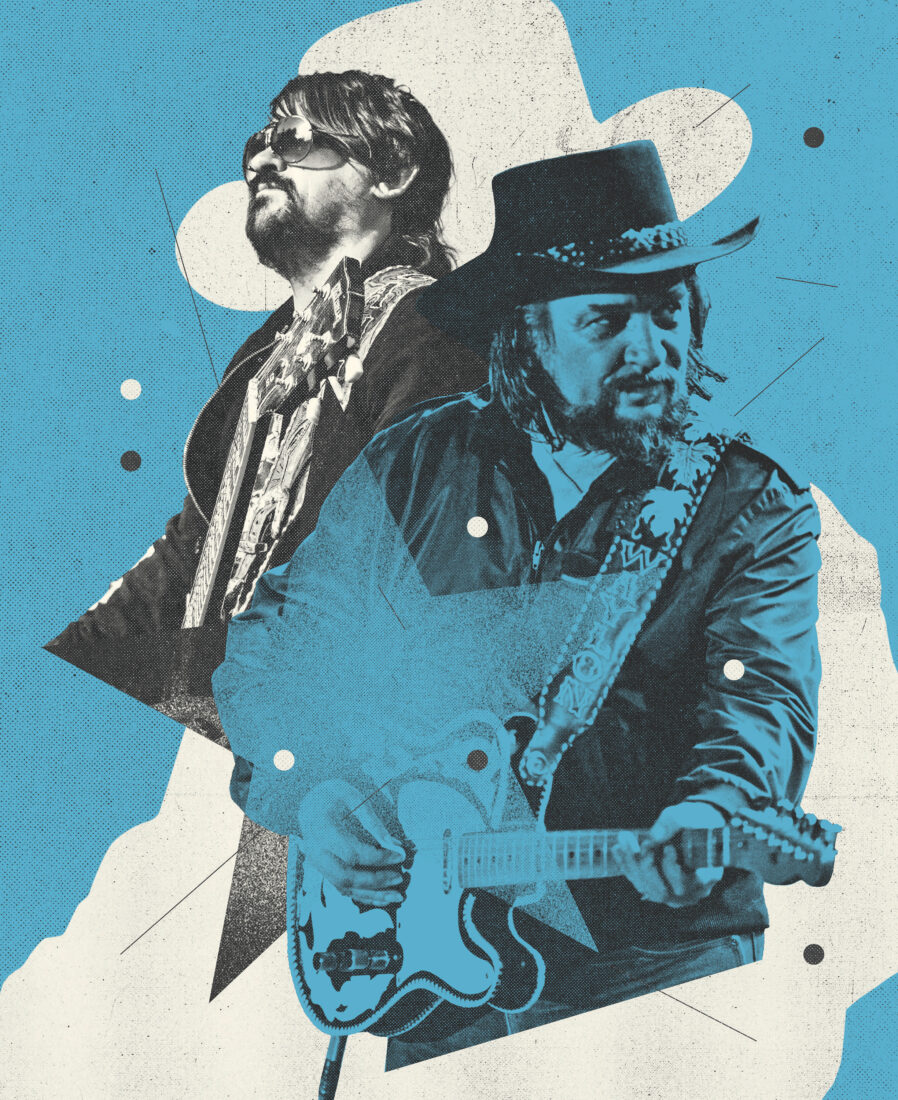

For the past several years, Shooter Jennings has been an in-demand producer, working with the likes of Brandi Carlile, Tanya Tucker, and Charley Crockett. But with some rare free time in the summer of 2024, he began tackling a project that had been gnawing at him: sorting through hundreds of finished songs recorded by his late father, Waylon Jennings, that had sat untouched since getting transferred to digital drives in 2008. As Jennings camped out at L.A.’s Sunset Studios 3, it felt, he says, “like going through a box that has this whole chapter of your father’s life in it that you never knew.”

Songbird—out in October—is the first result of that work, and a shoo-in for best country album of the year lists. The ten songs, recorded from 1973 to 1983, draw from a range of songwriters Waylon admired, and they counter his often-cantankerous public image with moments of remarkable tenderness, exploring themes of love, longing, and connection. “When somebody’s been gone for so long, the memory of them kind of distorts,” Jennings says. “There was so much more to him than the outlaw thing.”

The title track is a gorgeous take on the 1977 Fleetwood Mac classic, written by Christine McVie. “Brand New Tennessee Waltz,” by songwriter Jesse Winchester (whose songs have been recorded by Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, and Jimmy Buffett, among others), further showcases Waylon’s emotional depth, and it’s Shooter’s favorite song on the record “because of how vulnerable he is…and how good his voice sounds.” The delicate “Wrong Road Again,” made famous by Crystal Gayle in 1974, captures Waylon at his most remorseful, while a version of JJ Cale’s “I’d Like to Love You Baby” is a sly, come-hither invitation with a twangy bounce.

“What I drew from this was he was kind of the songbird,” Jennings explains. “He would go and cut everybody’s songs. If he liked it, he’d do it.” Jennings notes that Nelson also recorded a version of “Songbird” for his 2006 album of the same name, but he took delight in the fact that “Waylon had him beat by thirty years.”

Waylon famously had a contentious relationship with his label, RCA, but after beginning hard-nosed negotiations in 1972, he finally started to gain the creative control he wanted. He soon recorded Honky Tonk Heroes, a collection of songs written by a then-unknown Billy Joe Shaver, which essentially kicked off the Outlaw Country era in Nashville. For Waylon and his band, the Waylors, the period marked a remarkably fertile recording output fueled by cigarettes, cocaine, and the desire to capture lightning in a bottle.

Jennings confirms he’s planning to release at least two more albums from the trove. But there are also live recordings, side projects with Jessi Colter (Waylon’s widow and Shooter’s mother), and an unreleased album from the Waylors. Jennings estimates it will probably take him the next five years to sort through it all. For him, it’s about giving something back to fans who have kept Waylon’s memory alive. “They need to hear this because it will give them a whole other journey with him,” he says. “I think in this time we’re in and the way everything is focused on AI, this is a reminder of how it was done. This is the real deal.”

Plus: New Music from Madi Diaz

“Whose move is it to move on?” cries Madi Diaz at the close of “Hope Less,” the opening track on her devastating new album. Following the arc of a relationship’s disintegration and the subsequent fallout, Fatal Optimist is raw and sparse, mostly just Diaz and her acoustic guitar. “Feel Something” simmers with rage, the twinkling piano of “Flirting” signals a possible sense of calm, while the final, title track brings in her band for a declaration of healing. In less assured hands, Fatal Optimist could be suffocating, but Diaz’s finely tuned lines and turns of phrase ring true. It’s a stunning collection from one of music’s most impactful and deliberate songwriters.

(Photo-illustration: Shooter: Charlie Steffens/ZUMA Press Wire/Alamy; Waylon: Art Meripol; produced by Amy L. Diaz)