Sporting

A Lifelong Bird Hunter’s Farewell to Arms

A sportsman’s journey from the Alabama quail fields to the Canadian wilderness to laying down his gun

Photo: ALEXANDER WELLS

When he was a boy, my father came very close to shooting his own father in the back with a shotgun while quail hunting in North Florida. The incident haunted him for years, and he did not handle a gun again until he was a middle-aged man. When he finally did return to bird shooting, he did so with a grave attention to detail, and one of the details to which he attended most carefully was me.

I was twelve years old when he and a group of other men leased a twenty-thousand-acre quail-hunting plantation in South Alabama called Midway. The place came with a columned antebellum house; a cabin on a bass lake; a dozen or so good English pointers and setters; two red hunting wagons and four pairs of mules to pull them; horses to ride after the wagons; a number of men to drive the wagons and to train and handle the dogs—and God only knows how many quail.

For me, Midway was a paradise, and I wanted in on it. But though he wished for me to learn to bird hunt, my father did not yet trust me with a shotgun in the field. If he was a little more cautious on this issue than most fathers, he also had a right to be. I was a feckless, scatterbrained kid who believed there was nothing I wasn’t born knowing how to do—the type of kid who really does incline toward bloody accidents involving innocent people. My father had to deal with that fact, just as he had to deal with the memory of his stray shot in the Florida quail field and my nonstop pleading to be allowed to hunt at Midway. And so he came up with a solution. At the time I thought that solution cruel beyond imagining. Now I consider it the single most brilliant piece of parenting I’ve ever seen.

My father bought me a Crosman CO₂-powered pellet pistol and told me that as soon as I killed a flying quail with it, I could trade it in for a shotgun.

“A pellet pistol?” I yelped. Nobody, I pointed out, could hit a flying quail with a pellet pistol: I would still be trying when I was forty. I might as well have told him to consult my agent.

“If you want to hunt at Midway, it will be with the pellet pistol until you hit a quail with it,” he said. It would teach me safe gun habits and not to hurry my shooting. And it would teach me not to covey shoot.

“Not to what?”

“You’ll see,” he said.

That first season was an agony of embarrassment. There would be my father and his friends, some of them on horseback, some riding in the wagon; three pointing dogs on the ground, whipping like blown rags over the corn stubble, and three more in the kennel at the back of the wagon whining for their shifts. Out front on a spavined horse would be Fate, the head guide and dog handler, an old, thin Black man who knew most of what there was to know about mules, dogs, and quail. And thirty yards behind the wagon, trying at least to sit his horse well, would be me, truculent and ashamed.

Somewhere out front a dog would go on point, and Fate would raise his right arm. Whoever was driving the wagon would yell, “Whoa, mules!” and two men would step out and walk toward the point, cradling shotguns. When one of the men was my father, he would sometimes remember to turn and wave for me to come along, and I would jump off my horse, pull the Crosman from a sorry little holster, cock it, point it carefully at the ground, and run after him like a Pekingese. My father would motion me into an angle on the point from which I could not possibly shoot anyone. Then Fate would flush the birds.

There were big coveys then at Midway, and the quail would burst out from everywhere, sounding like a herd of horses snorting. There is still no other natural occurrence I know of as exciting and as difficult to watch as a covey rise: Thirty birds can all seem to blur into one and then be gone before you can blink. If you covey shoot at the blur, even with a shotgun, you can go weeks or even months without killing a quail. With a pellet pistol, I am here to tell you, you could covey shoot for decades without killing one.

It took me all of that first season and part of the next to make my eyes pick out a single bird from a covey rise and stay with it, blank out everything else around it. It took me most of the first season to learn to hold the one measly shot I had until a quail I was following had leveled out. And it took me two full quail seasons before I finally dropped a bird. I’m still not sure I killed it. A big pointer named Jim with a head like a splitting wedge brought the bird to my father, who had shot in the same direction I had. He turned the quail over in his hand.

“This the bird you shot at, Skip?”

“Yessir. Either that one or one that looked just like it.”

“It’s got a pretty big hole in its back. Must have been your pellet.”

He grinned and tossed me the bird. Someone could have opened it up and found the pellet if it was there. But no one felt inclined to do that, least of all me.

The next week my father gave me his 16-gauge Winchester Model 21 side-by-side, which I shot for the last weekend of that season and for the next sixty years at everything smaller than a goose. It is now worth ten times what my father paid for it and much more than that to me, but not as much as the lesson that got it for me.

Over the next few decades, I made a pig of myself at a movable feast of bird shooting. I traveled to Mexico for volume white-winged dove shoots; to Montana and Idaho for pheasant, sharptails, and chukars; to Argentina and Uruguay for doves, ducks, and perdiz; to the Bahamas for quail and pigeons; and to Africa for francolin. All this while continuing to shoot quail, doves, and turkeys in Alabama every year and waterfowl in Louisiana and Canada. I did much of this gunning at lodges or with guides and none of it with my own dog. While all of it was memorable, it wasn’t until I moved to New Hampshire and met Don Burke that I realized that what I had been doing was shooting, not hunting, and that in my scattered pursuit of it, I was guilty of the covey shooting my father had warned me about.

Don and I taught skiing together and came to be friends on the mountain. I did him the favor of introducing him to my sister, whom he married, and he did me the favor of introducing me to woodcock and ruffed grouse hunting behind his grizzled English pointer, Echo. For four Octobers before he and my sister moved to Vermont, we hunted every weekend. After the first season, I bought my first of many bird dogs, an orange-and-white Brittany named Buddy, and Don taught me how to train him. He also taught me how to recognize good covers and how to hunt them; how to look for the white splashes of woodcock droppings called “chalk” and the holes in the ground where they bored for worms; how to cut off a running grouse; how to wait in the infuriatingly dense alder bottoms we hunted for a flushed bird to tower above the treetops before taking your shot. In short, Don taught me how to bird hunt with a dog you had trained yourself. And that was all I wanted to do, and did, from then on.

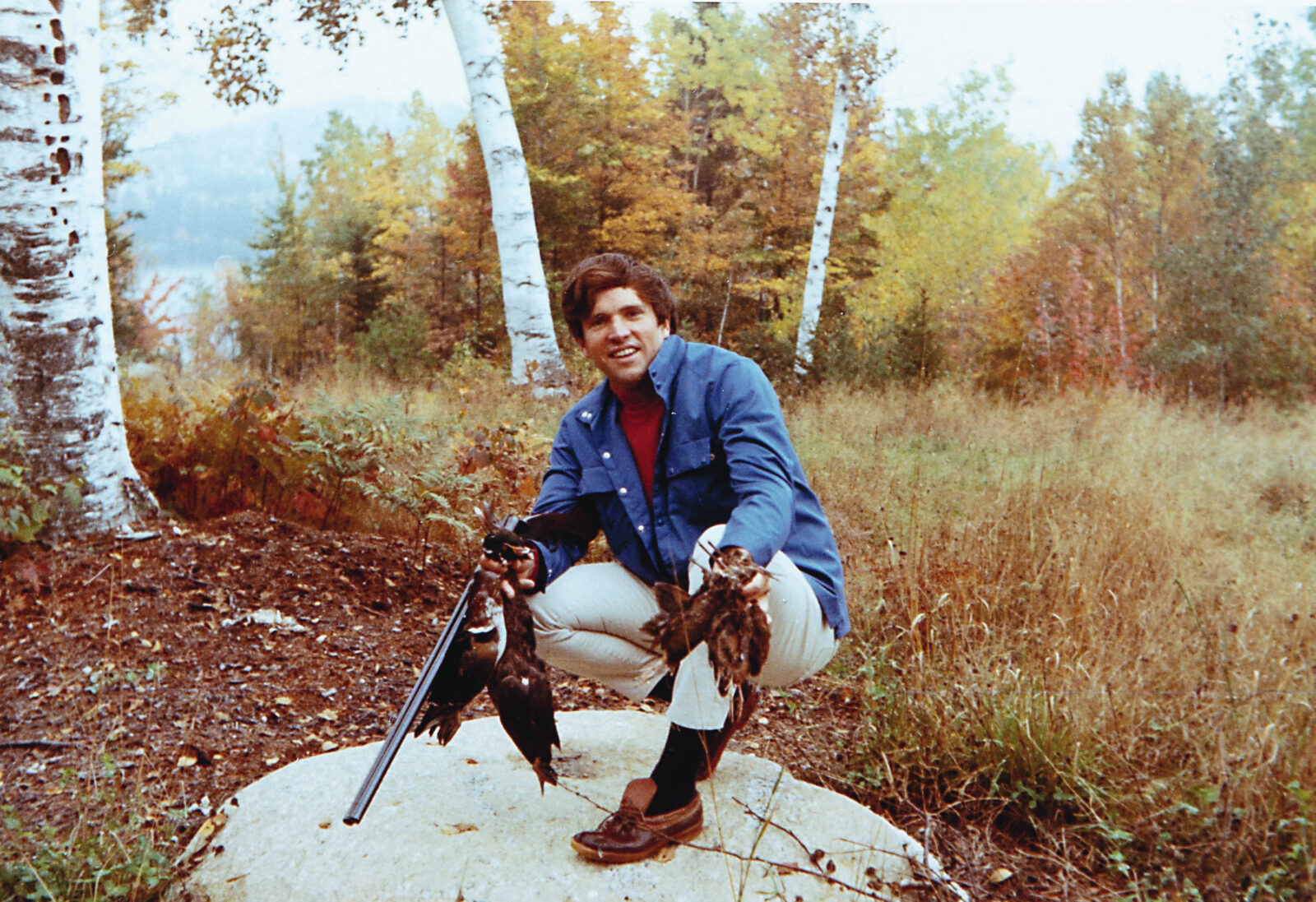

Photo: courtesy of Charles Gaines

The author (second from right) on a white-winged dove shoot with friends in Reynosa, Mexico, in 1969.

From 1979 until 2015, I went for one week every October to New Brunswick in Canada for its mother lode of woodcock, by then the bird I cared most about hunting. In those weeks, I feasted all over that vast, heavily wooded province with a blithe, indefatigable group of stalwarts, from writers to chefs: Chris Child, P. J. O’Rourke, Chris Hastings, Robert F. Jones, Ed and Becky Gray, Dan O’Brien, and Denton Hartley, to name a few. Back then you could hunt any New Brunswick land that wasn’t posted with a red disk—tens of thousands of acres, and we were the only bird hunters on them. Over breakfast we would divide up into groups of two or three, each with assigned known covers and a charge to find new ones, all of which we marked and described on the provincial topo maps we carried in each vehicle. We had good dogs, and we would hunt from early in the morning until dark, then return to whatever bleak little motel we were staying in with briar cuts on our hands and the dogs unable to keep their eyes open, clean the birds, pour red whiskey, and throw some protein on a grill.

We learned to look for tamaracks in the alders, south-facing hillsides of young poplar and birch, clear-cuts with three to four years of new growth in them, old gravel pits, and ridgeline evergreen covers when it rained. We often hunted all day in the rain, occasionally in snow flurries. And we and our dogs found lots of birds: In the hunting diaries I kept every year, I recorded many days of more than a hundred flushed woodcock and grouse, and we rarely ended the day without a limit of both. For the thirty-six years I hunted in New Brunswick, that limit was eight woodcock and four grouse per person a day. But by 2010, my own personal limit and that of anyone who hunted with me behind my dog was two and two. Shortly after that, for me it was zero and zero.

One day in New Brunswick twelve Octobers ago, I shot a woodcock over my English setter, Rebel. It was still alive when I picked it up. There was nothing special about that particular bird, but after I had crushed its skull with my thumb as I had done hundreds of times before, putting out the light in its miraculous eyes, I knew it was the last bird I would ever kill. And so it was, though I continued, and continue still, to bird hunt behind my dogs with a few old friends, but without a gun.

In rituals, the !Kung people of southern Africa become the giraffes and antelope they prey on. For them, hunting is an art, a transforming religion, and a way of life. Once, of course, it was those things for all of us: Our species’ first being was as a hunter; hunting was once our only occupation. Like our coccyx, the impulse still resides vestigially in us, and to awaken it, to bring the hunter in us out of his slumber and turn him fully loose, is a powerful thing that can transport us temporarily back to the domains of art, transforming religion, and a lost way of life.

A good and dedicated hunter first acquires skills. Then awareness. And it is that awareness that draws a broad line between hunting and shooting—or simply killing. The great nineteenth-century Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev wrote in Notes of a Hunter (perhaps the most vivid, erudite, analytical, self-questioning book ever published on the subject) that while engaged in hunting, the true hunter can come to occupy a state of venatic equipoise—a settling and focusing of the senses, a relaxation into primordial awareness and a balance of faculties that puts him in tune with the great watchful equilibrium of the natural world.

The Russian word for this state is okhota, which also denotes joy, and hunting on this upper level of awareness and poise can bring the hunter into a kind of macroscopic harmony, blending his awareness with that of the dog out in front of him, the circling hawk, the eyes and ears of the woods or field or marsh he is in. And that hyper subconsciousness, that too-temporary submersion into the natural world, is an addictive and magical drug. In its trance, you can do nothing wrong or awkward. The gun seems to lift itself, and if you are hunting with a good dog you have trained yourself, you feel you are two pairs of the same eyes and ears. Then, in the words of my late friend and mentor, and a sublime writer on the subject of hunting, Vance Bourjaily, “if a bird falls, it is like being able to bring back a token from a dream.”

To stick with and work at hunting long enough is to go from a tactical state of mind to the empathetic one contained in the word okhota, with the principal focus of that empathy on the bird or animal hunted. In the forty-plus years I hunted woodcock, I came to know and love their characteristics and habits as well as I know and love those of my dogs. It is always a mystery to those who do not hunt to hear from a hunter that he “loves” the quarry he pursues. Why, they wonder, would you kill and cause to suffer what you love? It is, admittedly, a riddle from the Sphinx, and every true hunter must sooner or later answer it in his own way. Posing the question to himself in his classic book Meditations on Hunting, the Spanish philosopher and essayist José Ortega y Gasset wrote, “One does not hunt in order to kill; on the contrary, one kills in order to have hunted.” For decades that was true for me and all the answer I needed to the riddle at the heart of hunting—until it wasn’t.

Photo: courtesy of Charles Gaines

Hunting ducks and woodcock in New Hampshire in 1970.

In my case—as in that of almost every contemporary friend of mine who has hunted all his life—to quit killing was not a mental decision, but a steady, undetectable progression from empathy to love to pity to something like reverence for what I hunted that manifested as a gradual deceleration of appetite to a stop, rather like the body coming to be full at a feast. For a number of years before I left the groaning board, my shooting deteriorated from the adequate it was at its best to poor, to poorer, and finally to missing a grouse sitting in an apple tree. Like overeaters everywhere, I was full before I knew it. But my heart knew it and was flinching, raising its eyes off the rib of the barrel, stopping its swing—saying, then shouting until I finally heard it, that it was time to put down the fork.

Since then, what I have found with some surprise is that I do not have to kill in order to have hunted. Now I go gunless into the October woods with my dogs and one or two armed friends, and revel in those woods and in the hunt as much as I ever did, finding, as did Tennyson’s Ulysses in that greatest of old-man poems, that “tho’ much is taken, much abides.” What abides for me is the Canadian autumn blaze of poplar, maple, and birch; the click of double guns closing as my friends walk in on a point; the unspoken choreography of movement in the woods among men who have hunted together for decades; the flush and flight of the birds; and above all—what was always the preeminent joy for me—the dogs carrying out what centuries of breeding bids them to do: the setter’s sudden quickening on scent, then stiffening into point; the cocker’s fierce and thrilling exuberance on flush and retrieve.

I see and feel those things more sharply than when I carried a gun. If for me, unarmed, the gate is up on the fully immersed rapture of okhota, they are all I want or need now from hunting birds. And each time I do it is, in itself, like bringing back a token from a dream.